The wild story of Jimmy Carter’s first election

Yesterday, former President Jimmy Carter passed away at the age of 100. He obviously had an extraordinary life, but for true election nerds, one episode stands out as particularly remarkable, dramatic, and unbelievable: his first election for state Senate in 1962.

The 1960s were an important threshold for American politics. They are still within living (though less and less each day, clearly) memory, but they still contained the last gasp of practices that feel completely foreign to us today, such as—spoiler alert—blatant voter fraud and flagrantly unequal voting systems.

A canonical example of the latter was Georgia’s “county unit” system for deciding Democratic primaries. Under the system, primaries weren’t decided by who got the most votes; instead, this twisted version of the Electoral College allocated a certain number of “unit votes” to every county in Georgia. Urban counties were worth six unit votes each; mid-sized counties were worth four unit votes each; and rural counties were worth two unit votes each. Like in the Electoral College, candidates would win a county’s unit votes if they carried the county, even if just by a plurality.

The problem, of course, was that urban counties in Georgia had a lot more voters than rural counties. For example, in the 1960 census, the three smallest counties in Georgia had a combined population of 6,980, while Fulton County was home to 556,326 souls. Yet they received the same number of votes in the county unit system.

With the Democratic primary tantamount to election in Georgia at the time (and with the system giving rural white votes way more representation than urban Black voters), the county unit system was wildly undemocratic. It was finally ruled to be illegal in 1962 on the basis of the Supreme Court’s famous one-person-one-vote ruling in Baker v. Carr. For the first time in decades, the popular vote would decide elections in Georgia.

It was under these circumstances that Jimmy Carter decided to run for state Senate.

In today’s era of permanent campaigns, the most extraordinary thing about Carter’s first campaign may very well be how short it was. Carter decided to run for Senate on October 1, 1962—just two weeks before the Democratic primary on October 16 (granted, this was later than the usual September date because of the upheaval in the electoral system). As Carter wrote in his 2015 book “A Full Life: Reflections at 90,” he didn’t tell his wife Rosalynn in advance that he was running; when he got up that morning and put on a suit and tie to head down to the courthouse to file to run, she asked him if he was going to a funeral. (Don’t worry, though: When he told her the real reason, she was excited by it—at least, according to Jimmy.)

The district Carter ran in, Georgia’s 14th Senate District, covered about 75,000 people across seven counties: Chattahoochee, Quitman, Randolph, Stewart, Sumter, Terrell, and Webster. Carter’s hometown of Plains was in Sumter, the largest county in the district; his opponent, Homer Moore, hailed from Stewart County at the western end of the district. Carter was optimistic about a victory because, as he wrote in his book, “Each of us had a natural advantage in our home community, and I already knew a lot of farmers and Lions Club members. Another key factor … was that members of our square dancing group came from most of the same area that the senatorial district covered, and they gave me strong support.”

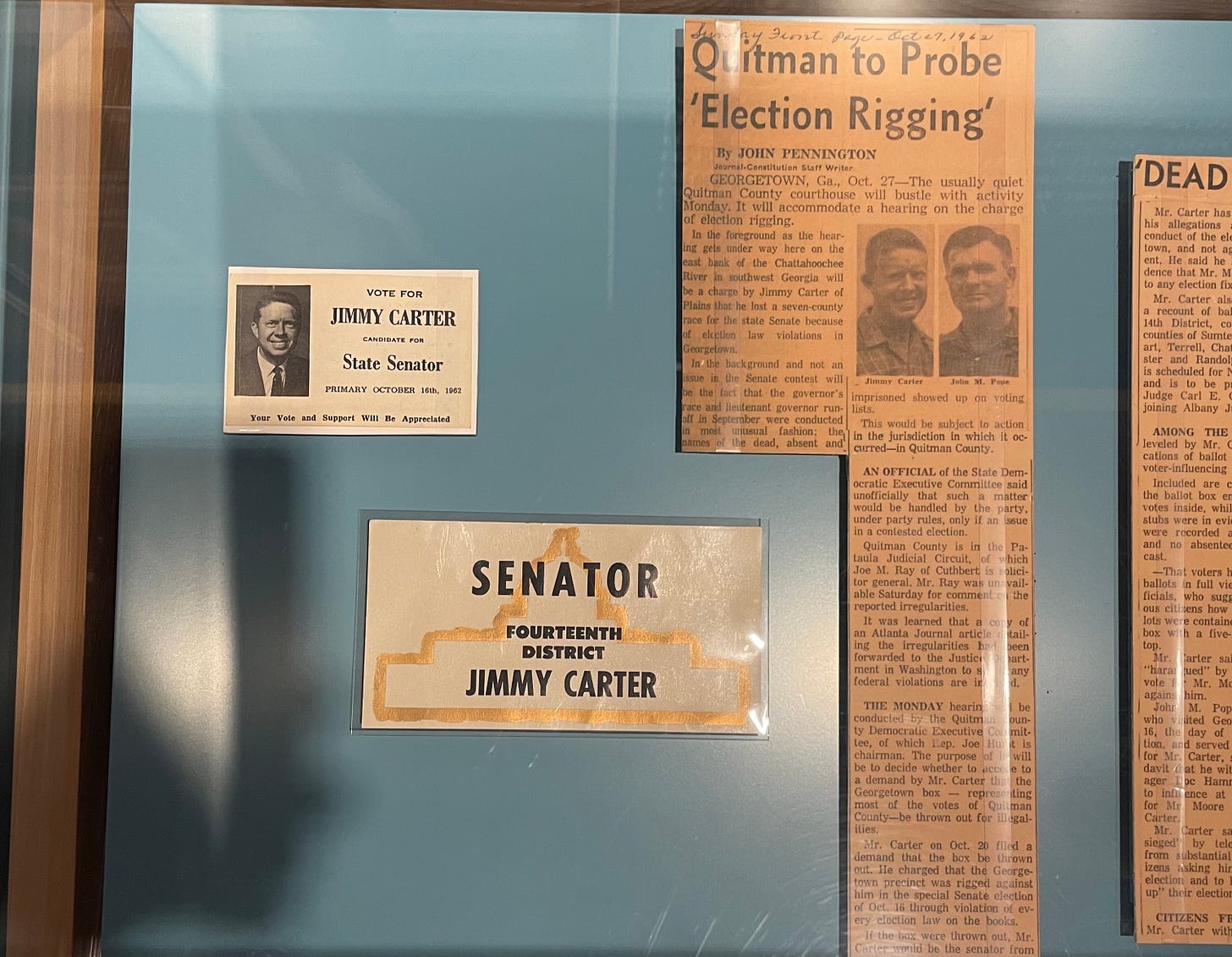

Indeed, Carter may well have won in a fair election—but instead, the race was tainted by fraud. On the day of the primary, a friend of Carter’s reported that Joe Hurst, the chairman of the Quitman County Democratic Party, was requiring voters in Georgetown to fill out their ballots in front of him—and telling them to vote for Moore. If they didn’t, Hurst would simply stick his hand in the ballot box and take out the offending ballot.

Outraged, Carter drove to Georgetown and confronted Hurst. But Hurst shrugged it off. According to Carter, “He responded only that this was his county, he was chairman of the Quitman County Democratic Party, and this was the way elections were always conducted.” When Carter called a local reporter to expose Hurst, the reporter just laughed that “Old Joe” was up to his old tricks.

The fix appeared to be in. When returns came in from the other six counties in the district, Carter led by 75 votes (2,778-2,703). But Quitman County voted for Moore 360-136—even though only 333 people had voted. A reporter for the Atlanta Journal later found that around 120 voters in Quitman County had allegedly voted in exact alphabetical order—and many of them were dead, in prison, or didn’t live nearby.

Carter was determined not to go down without a fight. He filed an appeal with the executive committee of the Quitman County Democratic Party, which consisted of Hurst and his cronies; it was unanimously rejected. Undeterred, Carter then filed for a recount, which would be overseen by a more neutral judge. He lined up several sworn affidavits from Quitman County residents corroborating the allegations of fraud; meanwhile, Hurst’s side insisted that everything had been above board and that all ballot stubs and voter rolls had been properly kept. There was just one problem: They couldn’t produce them. The whereabouts of the Georgetown ballot box were unknown for several days. Then, it finally turned up under, of all places, Hurst’s daughter’s bed. In it were about 100 ballots—but no other documents to support Hurst’s case.

On Friday, November 2—just four days before the general election—the judge made his ruling: The voting in Georgetown had not been legitimate, and those totals were to be ignored. Carter had outpolled Moore districtwide 2,811-2,746 (counting three smaller, non-Georgetown precincts in Quitman County). The state Democratic Party and secretary of state both declared Carter the Democratic nominee, and with no Republican running in the general election, Carter looked on his way to the state Senate.

Not so fast. Moore had appealed the judge’s decision, and late on Monday, November 5, a higher court ruled that the entire primary was invalid. There would have to be a revote, and in perhaps the most extraordinary of extraordinary moves, the judge decided that the new election would take place in lieu of the general election the very next day.

“I hadn’t been to bed for several days and had lost 11 pounds,” Carter later wrote, but he rushed back out on the campaign trail on November 6 for one (hopefully) last sprint. Every county posted similar vote totals to those from three weeks prior—except for one. Quitman County voted 448-23 for Carter. On his second try, he had won the seat 3,013 votes to 2,182.

Moore made one final appeal, to Lt. Gov. Peter Zack, the president of the state Senate, but it went nowhere. Carter was sworn in as a senator without incident in January 1963. He served there for four years, followed by four years as governor of Georgia, and then, of course, four years as president of the United States.

If you found this story interesting, Carter recounts the whole episode in detail in his book “Turning Point.”

Incredible story

Man, I imagine you’re not drowning in free time, but please keep posting articles on Substack. Loved this!